Sigríður Björnsdóttir

‘My belief is that, from the beginning, everybody has art and creative power. Some do more of it, and it comes out more, but I believe everybody has an artist inside of them.’

Sigríður Björnsdóttir

Across it all, Sigga’s life reflects the deep connection between art and healing, a quiet proof that art can, indeed, heal.

Her journey as an artist who became a pioneering art therapist unfolds in phases. Sigga, short for Sigríður, began her early work in classical training and observation before evolving into a period marked by a symbolic, emotionally driven visual language.

As she began working with hospitalised children, her style shifted, becoming more intuitive. Over time, care, teaching, and creative practice came together. In her later years, her work became simpler and quieter, with a focus on process over perfection.

Driven by a deep desire to understand and support children, Sigga ventured into therapeutic techniques during a time when specialised care for ill or emotionally distressed children–and even the concept of art therapy–was virtually non-existent. This remarkable selflessness ran in parallel with her own creative success: over 700 artworks created over the course of her life.

She took the leap—gently, elegantly. In her quiet way of being, she offered materials without instruction, creating space for the unspoken to be expressed. This is how she changes lives.

Born in 1929 in southern Iceland, Sigga spent her early years moving across rural parishes where her father served as a clergyman. When the family settled in Reykjavík in 1940, she was ten years old and already observing life through the eyes of an artist.

For a period in her life, she shared her path with her husband Dieter Roth, a Swiss artist known for his experimental and often provocative work. Their time together was one of creativity, complexity, and mutual influence.

Today, Sigga and Vera sit together in the apartment on Öldugata 17, where Sigga now lives, a quiet, light-filled space in Reykjavík’s old west side, close to the sea.

Vera followed a unique path of her own, studying geology before moving into filmmaking and cultural research, all while raising three children. As Sigga’s daughter, she holds unique memories—seeing not just the artist, but the mother: inspiring and profoundly human.

Here, mother and daughter look back and reflect on art, motherhood, and the delicate balancing act of being a creative person, a mother, and a giver.

Film by David Wirth

Shot at Sigga’s home on Öldugata 17, Reykjavík, over a coffee pause in the summer of 2024.

Sigga in conversation with her daughter Vera

Discovering Art and Its Healing Power

Vera: How did you get into art?

Sigga: When I was a child, I lived in the countryside with my parents, Björn and Guðríður, where my father was a clergyman. Before that, he had studied in Copenhagen.

Vera: Studied what? Natural science?

Sigga: Yes, that’s about right. He knew a lot.

I think I was around ten when we moved to Reykjavík. We were all living there when Iceland became occupied by the British Army during the war. Then came the American Army. The streets were full of these soldiers.

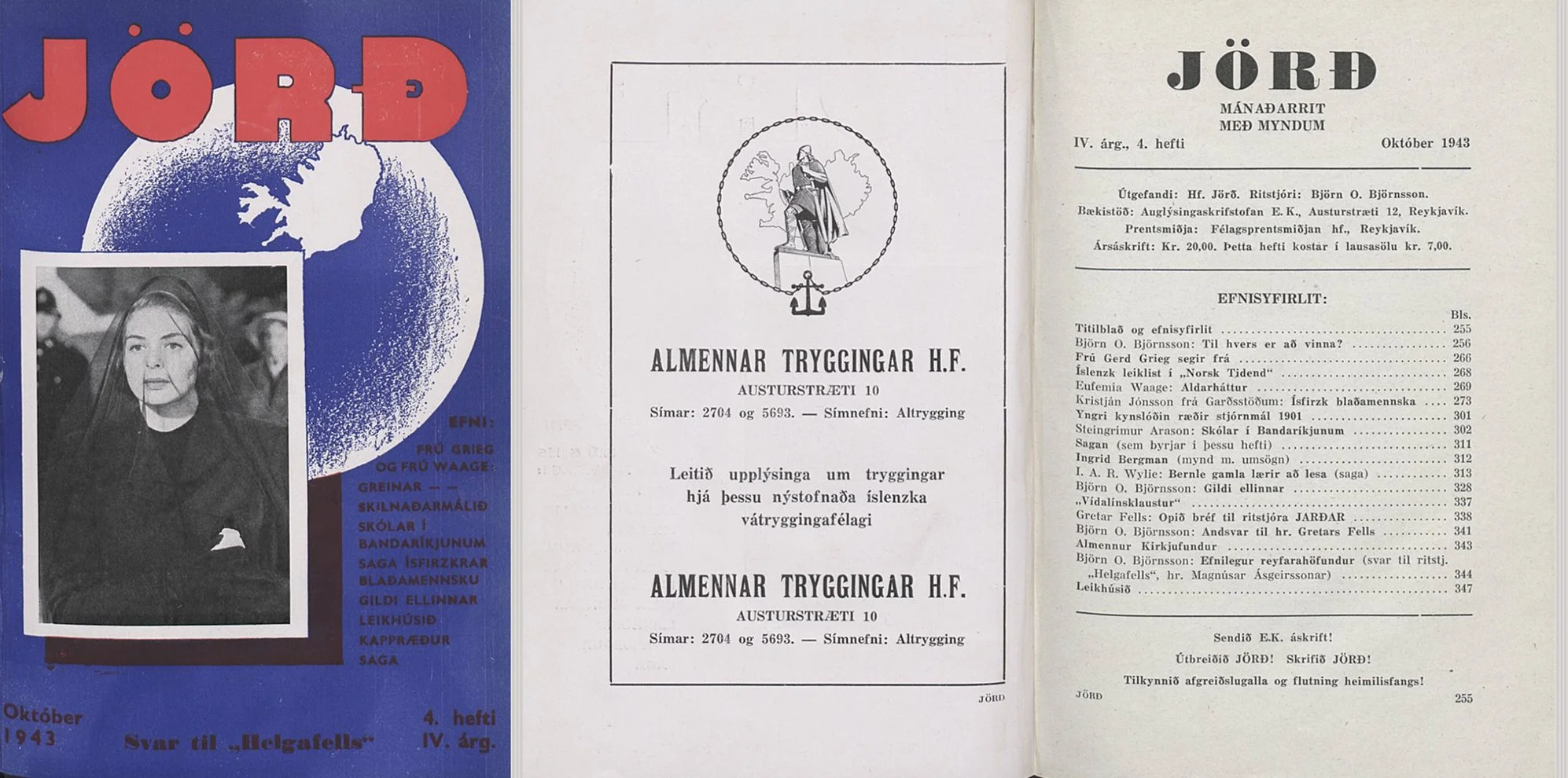

This was when my father stopped working as a clergyman and began publishing a magazine called Jörð (Earth). He worked on this magazine for many years.

At some point, he sent me and my brother to a children’s art school.

It was then that I started to paint.

From Artist to Educator

Sigga: Later, as an independent young adult, I was still interested in going to art school, and so I did. I was nineteen when I signed up at the painting department.

Around that same time, something unexpected happened. I became pregnant with my boyfriend, and shortly afterwards, we separated. I was about to become a single mother. I felt that I must be responsible for the child, so I must have some security. This was when I changed my course and applied to the teaching department.

I remained committed to the path I had set out on, with my parents helping to care for my daughter, Adda. In 1952, I returned to the Reykjavík College of Art and Crafts to continue my training. This time, to become an art teacher. I was twenty-three when I obtained a formal teaching diploma.

I started teaching children, and the natural interest children show in art awakened my desire to learn more about becoming an ‘art therapist’.

As part of our teacher training, we were assigned practical placements in various settings, but never hospitals. Even when I had my diploma as an art teacher, we went to all kinds of schools and institutions, but never hospitals.

So, I decided to go to London and get into a school, the Central School of Art and Crafts (now known as Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design), where I would have the opportunity to go to hospitals and support children. I talked to the British minister in Iceland, who arranged a very good opportunity for me.

He found accommodation and an opportunity to work in both a general children’s hospital and a hospital for physically disabled children.

I worked like this, training, for a whole year unpaid. But I didn’t think about money, as I had money from home.

Vera: Money from home? From whom?

Sigga: I had been working as an art teacher at the Women’s College in Reykjavík from 1952 to 1953, and since I wasn’t spending much, I never really needed to earn money.

Besides, this was the experience I had been looking for! I was working in the children’s departments at the Maudsley Hospital, which was a very famous hospital for children with psychiatric needs.

This was a time of learning for me. It was a wonderful time.

Before Art Therapy Had a Name

In hospitals, I worked with children who were bedbound, as well as those who were up and about but had very little space to work. When I arrived and approached the children in their beds, they were often hiding under the blankets.

I learned early on that what mattered most was not giving instructions, but creating the right conditions. I stressed the importance of letting the children paint freely. My role wasn’t to give permission, but to make the opportunity visible. I had a working room where I always put paper up on the walls, so that the children could paint as high and as far as they could reach. Over time, the walls were filled with their work.

Vera: Oh! Was it a little bit like what you have here?

Sigga: Yes. Like I have here. I have the paper, so you can draw if you like, right before you go!

And anyway, I had a very good relationship with the people in the hospitals. They supported me and helped me. I always went to the highest person, the director, and told them I wanted to get training or practical experience working with children with mental health difficulties, physical illnesses, and disabilities.

In one hospital, for instance, in Great Ormond Street, some children were very ill from various causes. At the Maudsley Hospital, there were psychiatric problems, and it was very interesting to work with those children. I could witness their creative expression. In that hospital, I used an entire wall to work on freely.

Interestingly, art therapy, as such, was not recognised at that time. However, what I saw I could offer to children was art therapy*.

Vera: Yes, this is the way it was, right? And then, much later, the study of art therapy was created. I think you were 50 years old when that happened.

Sigga: I believe so… Yes. However, while working with art students and children, I quickly realised that my role was to be with them—to offer opportunities. So, they decided what to do—whether they would paint or not. And they always happened to paint!

I gradually realised that this was a therapeutic method.

*While the therapeutic use of art has long-standing roots, art therapy was formally recognised as a profession in the UK with the founding of the British Association of Art Therapists in 1964, and in the US with the creation of the American Art Therapy Association in 1969. Early pioneers such as Adrian Hill, Edward Adamson, Margaret Naumburg, and Edith Kramer laid the groundwork from the 1940s onward—often working in hospitals and mental health settings, much like Sigga during her time in London.Vera: And you were the pioneer in creating this!

Sigga: Yes, that’s right. I also met a lady, Edith Kramer, who lived in the United States.

When I met her, we found out that we worked in very similar ways. On one occasion, she came to Iceland and stayed with me for two weeks. We had a lot of fun together. We used to write letters to each other.

Vera: Is this the background of how the therapy came about?

Sigga: This is how I realised, finally, that what I was doing was therapy, yes!

Sigga’s Method: Letting the Children Lead

Sigga: My belief is that, from the beginning, everyone has art and creative power. Some do more of it, and it comes out more, but I believe everybody has an artist inside of them.

This is why I never praised my students, or patients. I never said things like: ‘Oh, it’s beautiful,’ or ‘You’re doing very well.’ I simply showed interest. I would let them know that I was happy to see them doing what they were doing.

Vera: What do you think are the biggest misunderstandings about art therapy? Or about how people teach children in general?

Sigga: The most important thing in art therapy is to allow the person you’re working with to feel that you trust them. The therapist brings the material and creates the environment for the patient to paint.

So, for example, if children were confined to bed, my role was to put something down to protect the sheets from spilled paint. If they couldn’t sit up, I would help them find a comfortable position. I would arrange the bed, place the paints on the paper, and wait. I never said, ‘Now you can paint.’ The child knew, simply by the way I had set everything up, that this space was ready for them to paint.

Vera: The lady who wrote the book Art Can Heal was a former student of yours, Ágústa Oddsdóttir. Correct? Were there any other students, or children, who made a big impression on you?

Sigga: Yes, of course! There was a child in London, a boy I remember. He and some other children were very passive when I first started working with them, but they reacted so well to my approach. The boy was amazed when he had finished his picture.

Vera: Why was he so passive?

Sigga: Children in hospitals…you need to understand that there wasn’t much done for them. They were just lying in bed. They had nothing to do, nothing to inspire them. Everything around them encouraged them to be passive. Only doctors and nurses came by regularly.

Some children were very hesitant at first. But once they took their first step, something shifted. They found courage. It really was a fascinating process.

Balancing the Roles of Mother, Artist, and Therapist

Vera: How did you find a balance between working with children as an art therapist, supporting your own children at home, and creating your own art and poetry?

Sigga: It’s amazing. I never bothered with anything. I just did things without thinking too much. I did what I enjoyed! Sometimes I did things I probably couldn’t do, but I took on the challenge anyway.

I was very busy—working at the hospital while caring for the children and the home, but I was healthy and I didn’t worry about anything. Well…I worried about one thing. You children!

Both Dieter and I were brought up in a way that the husband didn't do anything in the house. The woman did everything. We were both brought up like that.

He liked to bathe the children and put them to bed in the evening, but after this, he often went out and maybe didn’t come back until midnight or one o’clock. This made me feel very sad and unhappy, with the children asleep and him gone.

Vera: A tough time. Did you sometimes make your own art and poetry in those evenings at home?

Sigga: Yes, of course! I did that very often, rather than sitting and crying. Dieter liked what I was doing, and he often put it up on the wall to show me that.

Vera: And did your work in the hospitals, doing art therapy, influence your own artistry?

Sigga: I cannot say what influenced my art or encouraged me to…I don’t say teach my art, even though I’m an art teacher. I never believed in teaching art, but in providing the opportunities to create it.

Anyway, it was fascinating work, really. All very successful and very wonderful. Big fun.

LEARN MORE ABOUT SIGGA’S LEGACY

‘Dieter Roth in My Life: Memories’ is a rare and intimate testimony—an honest and deeply personal account of a chapter in Sigríður’s life, shared with Dieter Roth, whom she describes as the love of her life.

'Art Can Heal: The Life and Work of Sigríður Björnsdóttir’, by visual artist Ágústa Oddsdóttir, conveys the lasting impact of Sigríður’s art therapy, as experienced by Ágústa and many others.