Eileen Norton

‘I've collected all this art. I've met a lot of these artists. I’ve had a very interesting life. Who knew where my life would have gone? I never imagined this.’

Eileen Harris Norton

Eileen Harris Norton’s collecting and philanthropy began in the 1980’s, stemming from her interest in work by artists of colour (particularly artists of the African diaspora), women artists, and artists of Southern California.

As president of the Eileen Harris Norton Foundation, founded in 2009, she supports education, family, and the environment, and especially programs for low-income children of colour.

In 2014, Eileen cofounded Art + Practice in Los Angeles with artist Mark Bradford and activist Allan DiCastro. The organisation hosts exhibitions and events in Leimert Park, with a special interest in showcasing artists living or working in Los Angeles. Through partnerships—first with the RightWay Foundation and more recently with the Los Angeles–based organisation First Place for Youth—Art + Practice also supports the needs of foster youth (aged eighteen to twenty-four) through paid internships, scholarships, and other programs and opportunities.

Two recent books are devoted to the Eileen Harris Norton Collection: All These Liberations: Women Artists in the Eileen Harris Norton Collection (2024) and Destiny Is a Rose: Art from the Eileen Harris Norton Collection (Forthcoming, 2026). Through her extensive art-lending program, Eileen has loaned works of art to museum exhibitions around the world. She has also served on the boards of the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; the Studio Museum in Harlem; and the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York.

Here, she speaks with her Art + Practice co-founder Mark Bradford, a contemporary artist best known for his large-scale abstract paintings created out of paper. His work explores social and political structures that objectify marginalised communities and the bodies of vulnerable populations, and is typically characterised by its layered formal, material, and conceptual complexity.

Produced in partnership with Cal State LA Community Impact Media Program and Alumni

Eileen Harris Norton & Mark Bradford

in Conversation

Art, Hair, and Honesty: The Start of a Friendship

Eileen: I met you [circa 2000] when I was with two curators who worked for us, and we went to your studio on West Boulevard, and there were fabulous paper pieces.

Eileen: How many did I buy that day?

Mark: You bought two?

Eileen: I did.

Mark: And you were really sweet. You weren’t leaving without buying something. So I was like, “Well, how much money do you want to spend?” And you took me over to the side and said, “Honey, that’s not the way it’s done. You tell me the price.”

Eileen: Well, you explained to me how you made the paper pieces. I was fascinated by them. They were beautiful.

Mark: I didn’t know anything about you except the things that I heard about the Nortons [Eileen and her then husband Peter, of Norton-branded utility software]. So I had these big ideas of who you were, but not anything concrete. And you know what I thought? I was like, “I hope she’s not snooty, because if she’s snooty, we’re going to have a problem.”

Eileen: And then we came to your studio and it was full of stuff everywhere. I was fascinated by the paper pieces. I was like, “What is that? What did you use to make that?”

Mark: End paper. You know, the funny thing about end papers is that in the 1960s, they used them for wet sets. Then, in the ’80s, they used them for Jheri curls.

Eileen: I used to get wet sets back in the day.

Mark: And white women knew about wet sets. But they didn’t know about Jheri curls. Another thing I remember about you is the sweet essence you had when you got out of the car. I do remember that. I was like, you know what, this is a nice lady.

Eileen: Oh, well, I’m glad because it could have gone the other way.

Mark: Did we hit it off initially? I’m trying to think if we did. I was doing your hair.

Eileen: You insulted my hair.

Mark: I did insult your hair. That’s right. You were like, “Excuse me, I go to so and so and so.” I said, “Well, so and so is not doing your hair good.”

Eileen: And I said, “Can you do better?”

Mark: I said, “Absolutely!”

Eileen: Then I started going to the shop [Mark’s mother’s salon, where he worked as a hairdresser].

Mark: I was surprised you got in that car, and you would come right over to the shop, and you’d sit down with all the ladies.

Eileen: It was civilised. I think you had told them to behave when I came.

Mark: No, you might’ve just caught it on a good day. That’s all it was. You got it on a good day, girl. You can’t control people—not those girls. Maybe it was because you came in the morning, when it was always the retired crew… But what I remember the most is that I always felt, and I still always feel, comfortable around you, which means that you have to remind me of the women that I grew up with, because I grew up in an all-matriarchal environment with a very particular type of Black woman.

Eileen: Well, I was going to the hair salon, sitting there talking whilst you were doing my hair.

Mark: That's how we got to know each other—just talking.

Eileen: And then after a while, Diana, my daughter, said, “Oh wow, I want to meet Mark. I want him to do my hair.” So then I started bringing Diana. Gradually, that’s how the friendship grew, with Diana and then finally Michael.

Mark: I think I put some perm on your son Michael’s hair once.

Eileen: I remember that Christmas, you took a family photo of the three of us in the shop.

Mark: You would have a crisis in your life, and I would have my own struggles in my life. But I noticed you always kept it private. I think that when you observe someone else protecting their privacy, that’s when you open up more. So by the time we started thinking about Art + Practice, we had already kind of established that we had the same vision.

Building Art + Practice

Eileen: I remember in the early days when we first started Art + Practice, we had artists in residence, and then we started doing shows.

Mark: With the Hammer Museum?

Eileen: We had Charles Gaines do a show. John Outterbridge, too.

Mark: We’ve had a lot of people who have gotten more recognition from the shows.

Eileen: The shows that we did included artists like Adrian Piper, Maren Hassinger.

Mark: Can’t always have us going to the mountain.

Bring the mountain to the people.

Eileen: That’s right—absolutely! And beyond the exhibitions, Mark noticed he would see so many young people out on the streets during the day in this area.

Mark: Or hanging out in their cars, in front of the hair salon, in front of the theatre, or in the park. And through conversations, we realised that there was a huge need in this part of LA.

Eileen: And we partnered with an organisation [called First Place for Youth].

Mark: It's Art + Practice, but I guess it's all practice. It's a verb.

Eileen: Yeah, exactly.

Mark: Art + Practice was a three-pronged thing. You were always interested in education. Allan [DiCastro] was always interested in some form of activism. And I was always interested in art. We were all on the same page.

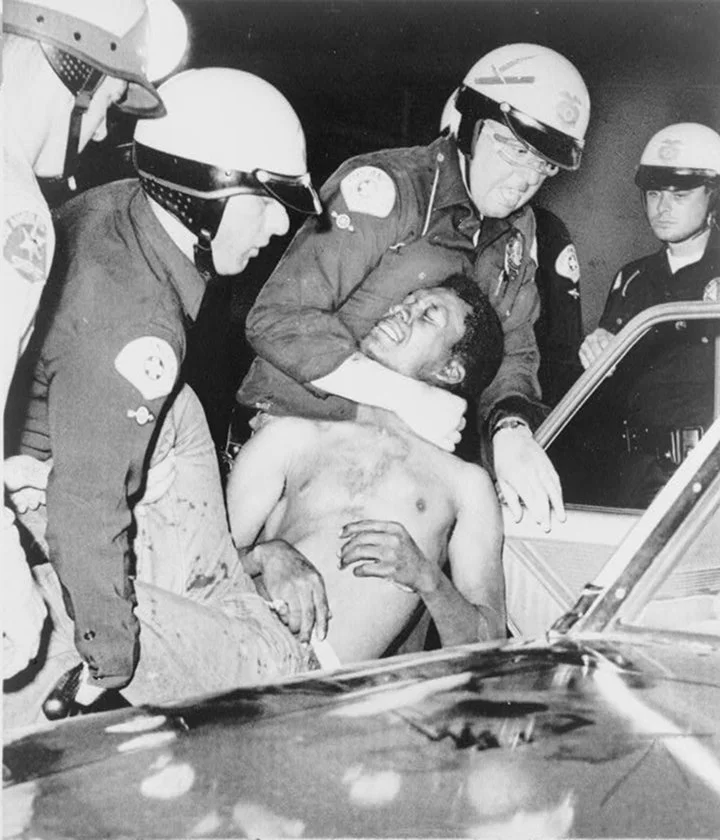

Watts Riots (1965)

Mark: But can you talk a little bit about Watts and 1965? Do you remember it? Does it play into how you think about activism and art? It’s a big question.

Eileen: Yes, I remember.

So back in the day, we called it The Riots. My mom and I were literally driving through when it was happening.

We were on the Imperial Highway, and it was on Avalon [Boulevard].

Mark: What'd it look like?

Eileen: It was just beginning. There were a few cars in the street, and the police. And there was not much of a crowd, so we thought it was just a car accident, but there were more people around, and the police were there, so it looked like something was happening. We looked and then drove on home. We were just a few blocks away, and then I guess by that evening it was popping off. Somebody had called my grandfather and said, “Turn on the TV, there’s something happening on Avalon.” We were like, “Oh, we were just there.” We saw those people in the street. Then it went on for days, and then there was a Safeway market down the street, and they started looting and setting it on fire. And I think my mom and uncles didn’t sleep for the next two or three days because they were watching. The rioters were throwing Molotov cocktails.

Mark: Your home was okay?

Eileen: It was. They had the hose ready in case somebody threw something in the yard. People were running up and down the street, driving up and down the street, because they looted the market and broke into the liquor store.

Mark: 1965 was really in your community. Do you think that had any impact on you?

Eileen: Well, my mom lost her job. She worked at that time at a pharmacy, and there was a ShopRite market next to the pharmacy on 120th Street and Central [Avenue]. They burned it down, and she lost her job. It affected us. Eventually, she got a job working at Thrifty’s. The community burned.

Mark: Yes. Just like in 1992 [during the riots following the police beating of Rodney King], it burned. And we had to move. We lost one shop. We moved because of the riots.

Eileen: You have done several pieces reflecting on civil unrest.

Mark: Oh yeah, The Rat Catcher of Hamelin (2011).

Eileen: But you’ve done others, too.

Women, Blackness & the Making of a Collection

Mark: Violence against women or civil unrest, are those some of the themes in your own collecting?

Eileen: I guess maybe underlying, so yeah, but I don’t think about it [like that]. There’s Kara Walker and Carrie Mae Weems. Those are themes in their work.

Mark: There are a lot of women in your collection, too.

Eileen: We purposefully collected women artists because women artists were underrepresented in museums and in collections.

Mark: So that was definitely a conscious thought?

Eileen: Women of colour was always a conscious thought.

Mark: What was the first piece of artwork you bought?

Eileen: I saw an article in the LA Times about Ruth Waddy, who was going to exhibit her work at [the Museum of African American Art in] the May Company department store. We were going to the mall, the May Company, all the time. But we didn’t even know that on the third floor there was a museum. So we went that day. There was Ruth Waddy artwork all over the walls. She was making linocuts right there, demonstrating how she worked. We talked to her a little bit, and then I stepped back, and my mom was pushing me forward, saying, “Talk to the lady. You need to get it, you need to buy something from the lady.”

Mark: Was that the first piece of artwork you bought?

Eileen: It was. I never knew any artists, and there was a middle-aged Black woman making art—about my mom’s age.

Mark: But you had been to exhibitions before?

Eileen: Well, yeah, to museums.

Mark: And did you see Black artists at the museums that really stuck out?

Eileen: Not so much.

Mark: You probably saw Norman Lewis.

Eileen: But not contemporary. I didn’t know of any contemporary artists…

Mark: You saw more Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence...

Eileen: Yeah. And it wasn’t until years later that I discovered Leimert [Park] and Brockman Gallery, and that’s when I met [its cofounder] Alonzo Davis and all the contemporary artists that he was showing.

Mark: Why did you pick Black artists, women artists, and artists from Los Angeles as your primary focus?

Eileen: Voilà… I'm a Black woman.

Eileen: I live in Los Angeles. I mean, that was it. With Peter, my ex-husband—we didn’t know anything, but we would roam around. We lived in Venice, where a lot of artists were living, but there weren’t any Black artists there at the time.

Mark: You were living in Venice and also buying from Leimert Park?

Eileen: That was part of our circuit. We would go to all the galleries. Back in the day, you could see all the LA galleries in an afternoon. There were all these artists opening their doors. You’d see their art, and it was like, “Oh wow, look at that.” We had no money to buy any art, but we enjoyed looking at the art and meeting some of the artists. Eventually, we could buy a little, and then it became a real thing.

Mark: Did you buy it for investment purposes?

Eileen: Oh, no. We never had any interest in investing. We were not buying artists that were blue-chip. Eventually, we belonged to some councils at LACMA, and then MOCA opened up, and it was a thing—we were the outsiders. People would look at us strangely. They didn’t even really want us to write a check to belong to the group. That’s how it was.

Mark: But were you comfortable being an outsider? You’ve been one pretty much your whole life.

Eileen: Yes, and so that was just one more place to be an outsider.

Mark: But don’t you think sometimes it also gives you a lot more freedom?

Eileen: Yeah.

Mark: Because you’re really not beating someone else’s drum.

The World Eileen Grew Up In

Eileen: I grew up in Watts, and my mom worked at Thrifty's, and my uncles worked at the post office.

Mark: Watts was different back then. It was just a working-class Black community. So you started going to stuff with your mom?

Eileen: Well… My mom was an interesting person. I think there was a lot of frustration in her life, you know? Her marriage didn't work out. She was very independent. With my mom, that was our activity. We would go to the museum, and we would go to the arts festival in Laguna Beach.

Mark: But how does a woman who works for Thrifty’s and two uncles who work for the post office have an interest in that? I’m not saying that we can’t… but how?

Eileen: That’s what they did. My uncles and my mom would go to the opera. Or go to the theatre or dance. We listened to the Metropolitan Opera broadcast on Saturday mornings. As a group, we would go to the theatre to see [dancer] Alvin Ailey. I always found that fascinating.

I think that my uncles, being who they were, created an environment of freedom. They went to World War II. After that, in the late ’40s, they came home, and one of my uncles wanted to be a radio broadcaster, but he couldn’t do that.

Mark: Because he was Black?

Eileen: Because he was Black, yeah. But there were three uncles. The one you knew was gay, he wanted to go to medical school, but that was a lot of studying. So he didn’t do that. He then became a bird-watcher.

Mark: Oh, he loved birds.

Eileen: He did. Because they were Black, there weren't as many opportunities. It was basically you become a doctor, a dentist, a lawyer, a teacher, work for the city, or work for the post office. So they worked for the post office.

Mark: I think you were always an outsider. That’s why you married Peter Norton. He was an outsider. We’re all outsiders.

Eileen: I always wanted to be a teacher because you know, I had a working-class family. And to them, you know, being a teacher, that was really important. I taught elementary English as a second language.

Mark: That’s a very unusual thing for a Black woman to be doing in the ’70s.

Eileen: That was during the wars in Central America, so there were a lot of kids from El Salvador and Guatemala. The LA school system was expanding to teach all these kids, and they spoke no English. UCLA had started a program in teaching English as a second language, so I did that.

Mark: So, once again, not being a follower. Trailblazing. You’re really a very curious person, aren’t you?

Eileen: How do you mean curious?

Mark: Well, you’re curious. I mean, why did you start collecting art? Or why Art + Practice? Do you read a lot?

Eileen: I don’t read as much as I used to.

Mark: But you've always been a reader?

Eileen: Yeah, I was always a reader. For mom and I, that was one of our big outings. Every week, we would go to the library. I also worked at the Watts Library while I was in school. And today, living with all this art, it’s something hard to describe. Every piece carries a personality. Melvino [Garretti], for instance, from Leimert. And Ramsess too; we met him through Art + Practice. Then Glenn Ligon.

Living with the Collection

Eileen: When I look around, I don’t just see objects; I think of the people, the presence of the artists themselves.

Mark: Because the work holds who they are.

Eileen: Exactly. So many of the works here in the house are tied to stories.

Mark: And to connections. I remember introducing you to Jack Whitten.

Eileen: Yes. And David Hammons, still working, still pushing boundaries. The art isn’t separate from the lives around it; it’s the relationships, the history, the memories. Like Chris Ofili’s work, which carries so much history. And Amy Sherald, who painted Michelle Obama’s portrait. We knew her before all the recognition, when she was still grinding away. It’s extraordinary to see someone working quietly for years, and then suddenly the world sees them.

Mark: Overnight success! Though my own wasn’t exactly overnight.

Eileen: A long time ago, Thelma Golden was looking for [her exhibition] Freestyle [at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2001], and that put you on the map.

Mark: It did. I mean, I got the call, but you have to understand something. To me, all of you guys were not people. You were godlike. Remember I showed you a picture of me and Thelma on the stairs at the Hammer Museum? That was actually the first place I ever saw her, standing at the top of the Hammer steps when the Black Male show [curated by Golden] was there [in 1995]. I had somehow gotten an invite.

Eileen: Yeah, because we supported that show.

Mark: You mean paid for it?

Eileen: Oh, ouch. I didn’t say it like that.

Mark: Honey, you wrote that check. You were writing a whole bunch of checks supporting people. And you know what? Just walking into a gallery and putting something on hold at that time, when we were really struggling with trying to get value in the art world, made a huge difference.

Eileen: It was a totally different landscape, especially for artists of colour.

Mark: But it’s almost like you kept hammering at it: They have value. They have value. They have value.

Eileen: And then that’s what gave us impetus to continue, because you and everyone—Glenn Ligon and Lorna Simpson, and even the Latino artists in town, Ken Gonzales-Day, Gronk, —we started seeking them out, and they were like, “Oh, look at who they are looking at.” We finally bought some Mike Kelley, and John Baldessari, too. But that was later, and not where we started. No, we were interested in the artists making the art of the day.

Mark: Everything you’ve talked about today really fleshes out the context of being a collector. It’s the context of your mother, your uncles, who you are as Eileen. You’re not only a collector, you’re an educator; you’re an outsider when you choose to be; you are a philanthropist; you’re all the things we’re talking about.

Mark: And I think that Art + Practice kind of…

Eileen: …pulls it all together.

Mark: It’s all kind of connected for you: education, philanthropy, community, liberation, civil rights, and driving past the ’65 riots.

Eileen: I always wanted to be a teacher. And I did that. I went to school, I became a teacher, but then my life went in a different direction, who knew!

Mark: But you’re still educating, Ms. Eileen.

Eileen: Then the collecting, where did that come from? I still don’t know. We were just looking, and then all of a sudden we said, “Oh, we have enough money, we could buy some art.”

Mark: You’re not a nostalgic person, really, are you?

Eileen: No.

Mark: I’m saying that you seem to live very much in the moment. I like to bring up stuff, and you’ll always say, “Oh, Mr. Bradford! Been there, done that.”

Eileen: Well, there’s been a lot of water under the bridge.

Mark: But you really are a woman who lives in the present.

Eileen: I’ve collected all this art. I’ve met a lot of these artists. I’ve had a very interesting life. I never imagined this. I just thought I’d retire as an elementary school teacher!

Inside Eileen’s home & collection

Inside Eileen’s Home & Collection

Kara Walker came on the scene, she came on the scene, because the work was so in your face. Again, referencing our history, my history, because my great-grandparents were slaves.’

Eileen Harris Norton¹

‘Alma Thomas was a school teacher in Washington, D.C. I saw a photo of it in the White House dining room, the Obamas were having a dinner party.

I started making inquiries about Alma Thomas, ’cause I didn’t even know her. And then, of course, her paintings became very popular, and I found one.’

Eileen Harris Norton

‘People would look at us and ask, “Who are you collecting?” And we said, “Lorna Simpson, David Hammons, Daniel Joseph Martinez.” They were all like, “What? Who?“’

Eileen Harris Norton¹

Lorna Simpson is another artist whom you’ve collected , basically from the beginning of her career to the present. (…) Lorna’s approach to centering Black women has inspired a whole generation of artists.’

Thelma Goldman¹

¹ All These Liberations: Women Artists in the Eileen Harris Norton Collection, edited by Taylor Renee Aldridge.

All These Liberations

Women Artists in the Eileen Harris Norton Collection

Since 1976, Eileen has collected art works by living women artists of colour.

Tanya Aguiñiga, Belkis Ayón, Sadie Barnette, Sonia Dawn Boyce, Iona Rozeal Brown, Carolyn Castano, Sonya Clark, Nzuji De Magalhaes, Xiomara De Oliver, Karla Diaz, Genevieve Gaignard, Aimée García, Deborah Grant, Renée Green, Sherin Guirguis, Aiko Hachisuka, Kira Harris, Mona Hatoum, Varnette P. Honeywood, Pearl C. Hsiung, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Samella Lewis, Maya Lin, Chandra McCormick, Julie Mehretu, Ana Mendieta, Beatriz Milhazes, Adia Millett, Yunhee Min, Mariko Mori, Wangechi Mutu, Senga Nengudi, Shirin Neshat, Mncane Nzuza, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Lorraine O’Grady, Ruby Osorio, Marta María Pérez Bravo, Adrian Piper, Calida Rawles, Faith Ringgold, Sandy Rodriguez, Alison Saar, Betye Saar, Lezley Saar, Analia Saban, Doris Salcedo, Amy Sherald, Lorna Simpson, Kianja Strobert, May Sun, Aya Takano, Alma Thomas, Mickalene Thomas, Fatimah Tuggar, Linda Vallejo, Ruth Waddy, Kara Walker, Carrie Mae Weems, Pat Ward Williams, Paula Wilson, Saya Woolfalk, Samira Yamin, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Brenna Youngblood

‘WOMEN ARTISTS WERE UNDERREPRESENTED IN MUSEUMS AND COLLECTIONS’

EILEEN HARRIS NORTON

BECOME PART OF EILEEEN’S STORY

To support Eileen’s endeavours, please consider donating or signing up to the mailing list at Art + Practice (A+P).

Based in South Los Angeles, A+P is a foundation that operates on a nearly 20,000 sq. ft campus with a dual mission: supporting transition-age foster youth and displaced children through partnerships with First Place for Youth and Nest Global, while also offering the public free access to museum curated contemporary art in collaboration with the California African American Museum