Celia Pim

‘In that act of mending, in that act of care, setting expectations and taking time to listen to the owners of the things I’m mending is very important.’

Celia Pym

Celia Pym is a London-based self-proclaimed ‘Damage Detective’. She sees beauty in imperfection; in tattered sweaters with frayed elbows, in moth-eaten cardigans ragged with wear. When Celia inherited her great-uncle Roly’s jumper, mended previously by Roly’s sister Elizabeth, her interest in mending was sparked. Two elements of the jumper especially moved her:

‘That the holes and damage were a trace of Roly’s body, evocative of how he moved and wore his sweater, and that the darning marks were evidence of Elizabeth’s care. These two ideas about care and the body written into worn garments have kept me curious for the past fifteen years.’

Inspired by the history and love woven into each repair, she set out to become an ‘expert in holes’. Since beginning her mending career in 2007, Celia has focused on repair as a way to explore a garment’s history of wear and how the moving body creates instances of deterioration. Through mending workshops held at Loop London and Hauser & Wirth, Celia shares her knowledge and skills, helping others mend and cherish their much-loved garments.

Her tools? Simple: Scissors, yarn, and a sharp needle.

Her work has been exhibited internationally most recently: Tipping Point, Frauenmuseum, Austria (2025); SOCKS: the art of care and repair, NOW gallery, London (solo) (2024); Bags, Hweg, Cornwall, UK (solo) (2024); Cheongju Craft Biennale, Cheongju, Korea (2023); ‘Connect. Reveal. Conceal’. Make Hauser & Wirth, London, UK (2023) ‘Threads: Breathing stories into materials,’ Arnolfini, Bristol, UK (2023); ‘Say Less’, Herald St, London, UK (2022); and ‘Keep Being Amazing’, Firstsite, Colchester, Essex, UK (2022).

In 2017, she was shortlisted for the Woman’s Hour Craft Prize and the inaugural Loewe Craft Prize. Pym is an Associate Lecturer in Textiles at the Royal College of Art.

Below, you’ll find Celia in conversation with Freddie Robins in Celia’s Islington-based studio, recorded exclusively for The Forgotten Her Story in February of 2025.

Freddie is an artist known for disrupting the perception of knitting as a benign and solely domestic activity, celebrated for her subversive knitting and embroidery, which often explores dark themes with a humorous twist. A Professor of Textiles at the Royal College of Art alongside Celia, Freddie has been part of the RCA faculty since 2001.

Celia Pym in conversation with Freddie Robins

The Start of Celia & Freddie’s Friendship

Celia Pym and Freddie Robins at Celia’s studio. Photo: Sarah Bates

Celia: I studied in the US between 1997 and 2001, then I went to Japan for a full year on a fellowship that supported a project to measure out a journey in knitting. When I came back from Japan, I got a teaching degree. I had a studio at Bow Arts Trust. I loved it. I was teaching part-time in North London and the rest of the time in my studio. I had a job that meant I could pay my rent and still left me time to make. Things were working out.

And then you got in touch, Freddie. You said, “I'm doing this show called Knit 2 Together, at the Crafts Council and we've heard about your knitting project around Japan.”

Celia’s piece at the Knit 2 Together Exhibition curated by Freddie.

Celia knitting in Japan. (2001)

Freddie: I co-curated Knit 2 Together with Katy Bevan, whom you and I have since done quite a lot of things with.

The Crafts Council just wanted us to make sure we'd really found as many different artists as possible, because obviously, your own networks are limited.

I've curated quite a few shows, and this one was fantastic to do. Even though you came relatively late to the scene, it was great because you offered something different to the exhibition. We didn't show any functional things, and that was something I was pushing for really hard.

Celia: It was a popular show, a big craft and art audience, which was something that was exciting to me in my early twenties. It had this massive breadth of reach, and it gave me a different respect and perspective on the textile skills I had.

I'd first learnt knitting from my home experiences, from my mum, my aunts, and my mum's friend Mary Ettling. Mary would stay with us from time to time, and I’d listen in as her and Mum talked about knitting projects. Planning their charts and debating what would be challenging in the pattern, and deciding what yarn they would use.

I think about knitting and its qualities of growth. Row after row follows each other, and cumulatively they add up to something bigger. That was what I was thinking about, measuring the journey around Japan in knitting. Step by step and row by row, the knitting was growing, the way days add up to a month and then a year. The stitches added up to this long piece of blue knitting.

The Imperfect

The Imperfect. The first collaboration between Freddie and Celia in which the artists explore the tension between perfectionism and imperfection in the context of knitted textiles created using advanced machine technology. Photo: Sarah Bates

Freddie: I call this project The Perfect, because the machine was designed to produce perfect garments. It’s a supposedly perfect system because there's no waste of yarn. The whole garment comes off the machine as one; nothing's cut nor sewn.

Celia: Then we called this one The Imperfect. We were using the knitted bodies that got caught or damaged by the machines in the process of making. It suited us as a partnership, because you were striving for this kind of perfection, while I had started mending things and was looking for imperfections.

The Imperfect. Photo: Sarah Bates

Mending by Celia Pym on The Imperfect. Photo: Sarah Bates

I'm interested in the question that perfection might be hard to attain and not satisfying when you get there. We're presented with so much imagery of how to be perfect in our physicality, our health, and in our behaviours. And it's impossible because humans are very imperfect. We could be far more generous with ourselves and our so-called differences or ‘flaws.’

I was also questioning whether an aspiration for perfection was desirable. With knitting machinery, the industry needs everything to be perfect and in repetition. This is important in manufacture—they guarantee that all the products will be the same, perfectly identical.

Freddie: I love that the digital can only replicate what we’re giving it.

The more you digitise something, the more you automate it, the less flexibility there is and the more you must explore the tension. However, when you are hand-knitting, you can manage each stitch separately. You can knit with more or less anything your hands can bear to knit with.

But the automated machines are very sensitive. What the machine does, when it gets to a certain area, it's like, “No, I've had enough of this. I'm not going to run this through. It's too tight, it's too heavy, or it's too much.” Sometimes the yarn may have a defect in it, and then it drops the stitch.

Celia: Yes! With our Waste Yarn Project blankets. These are digitally knit and because of the age of some of the yarns that we’re using, they’re snapping when they’re knitting up and we’re getting these wonderful broken areas in the knitting. It’s colours, like that brown, that are constantly snapping on our blankets.

Freddie: I think it's also often to do with the dyeing of a yarn in a different way. I love the way that yarn has a lifespan, too. Like human beings, it gets old and tired.

Celia: And that yarn has personality. It gets old and tired and then becomes brittle and breaks. But it is also flexible, folds and collapses.

Freddie: I love that about cloth. You can fold it up relatively small and then unfurl it, and it can suddenly occupy loads of space.

Celia: It’s magical like that.

I'm just so happy seeing [these bodies] again. I love them like this on the two tables.

Einband yarn. One of Celia’s favourites. Photo: Sarah Bates

The Imperfect and wool yarn from Iceland (Einband). Photo: Sarah Bates

Freddie: I’ve tried to avoid showing this work [The Perfect and Imperfect] in relation to the body, because knitting is always seen in this way, and I do not want to do functional things.

For quite a long time, people kept asking me to do functional things. I don't want to do that. You ask me to make a sweater, and I could, but that's not what I want to spend my time doing. Get someone who makes sweaters to make you a sweater.

Celia: There are challenges around displaying knitting and knitted work. I remember you and I talked about how if you use a coat hanger for display or anything that references what people usually associate with clothing, you immediately think you might be in a shop or in your wardrobe.

Then you think, I want to touch it or put it on. People can't get away from it being just something functional that they love and wear.

I've always thought these two bodies have a bit more… not to insult the others, but a bit more personality.

It’s all the same (installed in “New Doggerland”, Thames-Side Studios Gallery, London). Freddie Robins. (2019) Photo: Justin Piperger

It's all the same. Freddie Robins. (2019) Photo: Douglas Atfield

Freddie: Definitely. They're more one of a kind because they're the first ones that got made. They're mistaken ones, whereas the others did come out a bit more uniform. These were the test bodies, and these also have that tension between the hand work and the flat machine work. They definitely have a very different personality.

Celia: Freddie, you had that issue, when you were making them. You said, “There are so many possibilities for display and composition.” You just kept knitting them.

Freddie: I probably had about thirty, and some were joined together in this really large work where they're all holding hands, and I put them together, a bit like paper dolls.

Celia: But I love them super floppy like this.

Freddie: I do too. That's why I developed that piece where they're like paper dolls; they have no structure, and they just flop.

Celia: I also love that yellow thread and all these unfinished bits in The Imperfect.

Freddie: The yellow strip was about me trying to…

Celia: Were you trying to straighten the legs?

Freddie: I was trying to do something technical. I can't remember what now. Look how uneven they are. I must have been trying to measure something or trying to work something out that wasn't quite right. These bodies were early ones where there had been technical problems, which is why there were holes and then you mended them.

Celia: So, you would’ve added this thread after it came off the machine, right?

Freddie: Yeah. I put that through after they’d been knit.

Celia: These bodies and their damage was funny and a new challenge for me, because until this point, I’d only been mending clothes. You said, “Well, what about this? It’s got damage.” Which is what I’m attracted to.

I couldn't get my hand inside the bodies. What I thought at the time was that these imperfections were in the places where people might have grazed themselves, like the knee, or the wrist and palms, or cuffs which had been worn down and rubbed. I definitely remember mending that knee and feeling very tenderly towards this knitted body.

Freddie: The way the machine works, it was obviously more problematic on the extremities, like the arms and legs, while the solid centre seems to be okay.

Celia and Freddie discussing The Imperfect. Photo: Sarah Bates

Freddie’s yellow thread to straighten The Imperfect’s legs. Photo: Sarah Bates

Celia: It's like there are multiple partners on this project. Not only you and me, but also the technician and the machine.

I remember you speaking about convincing the knitting technicians you were working with that what you want to do is, in fact, what you want to do. Maybe persuade them to go against their instincts.

Freddie: And to go against their training.

Celia: That makes sense they're caretakers of the machines, looking after the machines and making sure nothing bad happens—no damage happens to them.

Unseen Textiles

Mended pieces by Celia. (2025)

Celia: I'm not a printed textile person. The bit that I like about textiles is the construction.

Within textile conversations, we often think around processes – we talk about print, weave, knit, crochet and embroidery. Studies and artists who work with textiles are sometimes understood in relation to those categories.

Constructed textiles and three-dimensional shape and form is exciting to me. I love the possibility of construction. It can be anything, depending on the weight of the thread or in the manner in which you’re building it. I start with a single line and make something physical and spatial. I can fill holes and make material.

Celia with some her pieces. Photo: Sarah Bates

We are so familiar with textiles, because we wear it, because it's under our feet, or because it's the dish cloth we use daily. When you dry your hands or feel the upholstery in the car that you sit in or on the tube, we don't even question how we know it. We just know it. We can sense how it will feel by looking at it.

Freddie: It’s visible, but often unseen.

Celia: That's a nice way of describing it.

Freddie: I've always been intrigued about why textiles are all lumped together.

Because it feels to me that if you are putting an image on top of textiles—you might be printing an image—that to me has very little relationship to constructing something. That's akin to printmaking or painting, where you have a surface and you put something on it, as opposed to starting with material and making something. Sometimes, I think that printed and constructed textiles don't belong together.

I can't do two dimensions. I even struggle with drawing. It's so flat, isn't it? It's just on the surface. I want to turn the page over or see the back of it. Drawing is so difficult and flat, unforgiving. Then you turn the page, and it's a white piece of paper, or a computer screen. I really love conducting materials.

Celia: Conducting materials is a lovely expression. You get your words out well, Freddie.

Freddie: Oh, you're so kind.

I suppose I think a lot about how you can talk about what you do without saying, “Oh, it's knitting or it's textiles.”

And I love the way that the needles are like wands, or like a conductor's baton.

Celia: I'm trying to knit a cable at the moment. It pleases me that that line becomes this solid textured, rope-like mass. I’m knitting it in dark navy blue.

One day, I'd love to do a project where I just knit all the material I've got in my studio. Turn everything into a thread or line, take a year and just make it all into material and mass.

Paper sweater with the knitted cable.

One day, I'd love to do a project where I just knit everything I've got. You know, take a year and just make it all into…

Freddie: God, you're getting knit-obsessed.

Celia: Yeah, I know.

Finger Magic

Freddie: I really love the idea that you can unravel what you've done. Although I never do. But I like that it's there.

Celia: When I started working with paper, and mending paper bags, the jeopardy was if you made a hole you couldn’t undo it. The pricked hole in the paper is permanent. Whereas the knitted loop can go backwards and forwards. Be made and unmade.

I love unravelling. I love when you unravel knitting, how the material has a kink in it from the looped structure. It's got a trace of the life of its structure.

Freddie: But you can get rid of that just by washing it, and you suddenly lose the evidence. Then I wondered if maybe that's why I like knitting, because I think I'm a really, risk-averse person. It feels safe for me.

Celia: I don’t often think about risk in terms of my own work.

I think about when things don't work or when trying something new feels risky. Maybe doing a residency somewhere feels risky.

Freddie: But you have done things where you get other people's items, and you have to repair them, and it can go wrong. Is that not a risk there because their expectation might be different to what you deliver?

Freddie’s family blanket mended by Celia. Photo Sarah Bates

Freddie’s childhood memories with the blanket. Photo: Sarah Bates

Celia: Yes, I suppose there is risk there. Managing an owner’s expectation of what mending can be achieved on their particular hole, how it will look and feel, is challenging. Also, what they hope for their damaged piece of clothing or precious textile.

I'm always curious about how a sweater with a hole in it offers an opportunity to talk about more personally difficult things. The damaged sweater acts as a stand-in and opens up a conversation about how they want it cared for, and why it’s important to them.

It’s taken me a long time to figure out the negotiation of what my boundaries are when I'm mending things for other people.

I put myself in a role. I am Celia, but I'm the mender. I understand the limits of what I can do in that role. In that act of mending, in that act of care, setting expectations and taking time to listen to the owners of the things I’m mending is very important. I have had to learn to do that. And make a boundary between the work and me.

Freddie: But they’re your boundaries, not someone's boundaries.

Celia: Yes.

Freddie: And you would never say to someone, “I really think you should give up on this sweater and just go to a therapist”?

Celia: Never. I appreciate the many opportunities where I have all these exceptional encounters with people through their clothes. I think it’s possible that a person's never spoken about a particular feeling or experience before and the circumstances of being invited to get their damaged item mended presents a distinct interaction. The invitation to having something cared for and mended seems to surprise people. They’re not quite sure how to react. People just tell me about themselves and their clothes, and I get to hold that for a little bit.

I'm curious about people, but I'm not burdened by what they tell me.

Freddie: And it's not a lifelong relationship.

Celia: No, it’s just that moment in time. The time it takes to mend the thing.

Ideally, the good bit is when an owner is surprised that the mending has transformed or added to their item and it’s shifted the way they felt about the damage. Sometimes people say, “This is really what I was hoping for.” Or, “I didn't know what I was hoping for, but I love this.” People often say, “I could never do that.”

I just think there are so many opportunities where I have all these odd encounters with people through their clothes. I think it’s possible that this person's never spoken about this weirdness before. They just told me, and I get to hold that for a little bit.

The reason it's not impossible to do is because I'm curious about them, but I'm not burdened by their confession or what they tell me.

Freddie: And it's not a lifelong relationship.

Celia: No, so I can hold it for that moment in time. Then I can mend the thing, and I can have this funny encounter where I'm looking at the garment and thinking, “God, who did this? How did this fit them?”

Or it really doesn't suit, and then you can give it back to them. Hopefully, the good bit is when it goes well and they're surprised by what they see and say, “This is really what I was hoping for.” Or, “I didn't know what I was hoping for, but I love this.” People often say, “I could never do that.”

“You have some kind of skill or finger magic.” Then I feel really good. I can do things for others.

Freddie’s blanket mended by Celia. Photo: Sarah Bates

Wool sweater mended by Celia. Photo: Sarah Bates

Subversion and the Politics of Craft

Weaved Floor Scraps

Freddie: I love the notion of our skills being magic, but then, it also worries me because people so often undervalue domestic skills, like darning or knitting. Quite often people who practice them really well will say, “Oh, it's easy.” That's not true because it's something that you've never received payment for. It's something you learn at home, so it's not valued as work.

Celia’s studio wall. Photo: Sarah Bates

Celia’s wool. Photo: Sarah Bates

Celia: One of my mum's best friends was Mary Ettling, I mentioned her already, she was an epidemiologist. She lived in Texas and Washington DC and for a period she worked for the WHO (World Health Organisation) in Malawi and Thailand. When she’d travel for work she’d often come through London. I loved her visits because being a highly knowledgeable person who did field work on mosquitos and disease seemed awesome. She was a great knitter as well.

She was so cool because to me she seemed very undomestic. Her life looked exciting from the outside. She was always a powerful role model of a woman who was financially independent, adventurous and did work she really loved.

Celia Pym. Photo: Sarah Bates

Freddie Robins. Photo: Sarah Bates

Freddie: She probably really struggled with being a woman in that field.

Celia: I can see that is possible. She was not like any of my mum’s other friends or women I knew as a child.

Freddie: I don't think I really thought about it [domestic skills] when I was a child, but I definitely thought about it as a parent; I didn't want to fit in with the other parents, but I didn't want Willa, my daughter, to be ostracised.

At the school gates you have to try and fit in because you don't want the other parents to think, “There's that really weird, annoying woman, and I don't want my child to play with her child.” I can totally understand that; really trying to fit in so that your child would be a bit better accepted.

Celia: When we hang out here like this, I don't feel like either of us has to conform. It's just that we get to be ourselves.

Freddie: I was in a show in New York, and I was showing my work and talking about it, and the curator said to me, “You can't make some work that's funny and some that's serious. You have to decide.” I really had trouble understanding this. I just said to him, “But sometimes life's funny and sometimes it's not.”

That's my experience of life. But it wasn't his view of how you had a practice.

Celia: It's sort of a limited comment, suggesting your work needs to be one way or the other. Are you the humorous artist who makes people laugh? Or are you the weighty, serious artist?

Stone (2024). Freddie Robins. Photo: Douglas Atfield

Llama (2023). Freddie Robins. Photo: Douglas Atfield

Freddie: They're not my rules, and I make things on my terms. And if they don't fit with other people's terms, then they don't fit with other people's terms.

More recently, I was talking with someone and I said, “Can you be really honest with me? Is there anything about my work that bothers you?” And someone said the humour. I was thinking, God, it really bothers people that sometimes I'm funny. Then I was thinking about the male artists who make funny work, but then I guess they always make funny work.

Celia: What I like about your work is that it lets me be closer to the sort of darker stuff.

Because of the manner in which you’ve made it – the colour choice or the way you've played with a word, or you've presented it not as a joke, but as something you make accessible through the familiarity of the knitting or form.

Freddie: I guess what I'm interested in is making dark things accessible. And again, back to this thing about subverting people's expectations of materials, of the knitting process, or of crafted objects. I suppose subverting people's expectations of women.

Everything is about that. But sometimes, I really wish it wasn't all about subversion.

3D paper and wool vest by Celia Pym. Photo: Sarah Bates

Celia: My friend said, “The studio's the place where you can be anything, you can do anything. The rules are entirely yours, and you can do anything.”

I really took that to heart. In here, new things could happen. New things that I have no idea about can continue to occur. And I can be exactly as I want in here. Wear messy clothes, work obsessively and late hours, change my mind about what I’m making or doing.

Skill is an easy entry point into valuing work. Like, “Oh, this person has put in 10,000 hours. They're so skilled at throwing stitching or weaving; we value their skill for that. For their dedicated hours.”

But the hours don’t necessarily make the work exciting; it is as if the skill is the thing that an audience is valuing. The commitment of time.

Freddie: It’s easier to say, “How long did that take?” or “How tiny were your threads?” As opposed to saying: “What does that mean?” “Why did you do that?” Those are all more complicated questions, whereas “How long did it take you?” is also something where you give something value.

Celia: Sometimes, there’s a hierarchy of where you learn the skills that correspond to value.. If you learnt it at home, developed it yourself somehow, or learnt it in a school, institution or apprenticeship.

Sometimes skill might look more raw but is in fact hugely refined.

I adore the work of Judith Scott. Her material skill, how she wraps objects and constructs her sculptures really move me. And is so distinctly her own mark of making. Though she doesn’t communicate about the work verbally the evidence of her skill and it’s knowledge is there in the work.

Freddie: That’s what I was going to say, just because she doesn’t verbally articulate it doesn't mean it's not real textile skill.

Celia: For me, the craft thing is about bodily knowledge.

“Nerve in your hand. One grows apart to let the other one through.” - Quote in Celia’s studio, an ode to her love for anatomy. Photo: Sarah Bates.

Wrapped Fly-Swapper, work inspired by Judy Scott. Photo: Sarah Bates.

How to make with your body, which isn't just the intellectual idea, but it's that blending of “I know what my hands are up to, I've had an idea, and I'm also executing it, and I know what I want the work to feel like and communicate.”

Sometimes, people respond to my very fine mending work as if it’s a more obvious skill. “Wow”, they say: “How did you do that?!” The category is clear, fine threads, fine weaving, fine fingers: high skill. But they don’t respond that way to the chunkier more expressive mends.

Freddie: Whereas with work like Judith’s, people can’t say, “I don't even know how she learnt that.” I can't categorise that. I'll just say it's outside or something. I can't box it. We’re obsessed with taxonomy.

Celia: If you exist outside, or if you live a life that doesn't fit in with majority systems, you aren't going to fit in any of the boxes.

On Caring

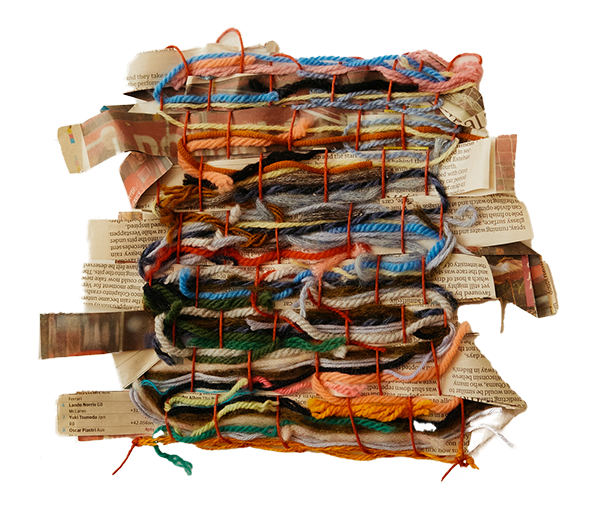

Weaved Studio Scraps

Celia: I am interested in this question of how you pay attention to something as an act of care. I'm curious about that. However, I’m awkward and less sure of myself when it comes to talking about gender relationships around care.

It often comes up for me: how do you feel about this role of being the woman who is doing the darning? I get really muddled by that because I don't recognise that as a description of myself. I just recognise myself as someone for whom it feels so natural to pay attention to damage, and then care for that hole or weak spot.

Celia’s cushion. Photo: Sarah Bates

Weaved scraps from Celia’s studio. Photo: Sarah Bates

I'm always attracted to the vulnerable and what can you do to work with it. What does care look like around that vulnerability? Whether it's sickness, whether it's a hole in a sweater, whether it's a faded bit of paper, or a paper bag that's torn.

I was doing an interview and someone said, “Oh, but how does that relate to your sense of yourself as a woman doing all this care?” I sometimes feel really stupid, if I'm honest. I don't have a good enough answer for it.

Freddie: But maybe that is the answer. It's just done because it feels right to you as a human being.

Celia: Precisely. I also think that, not having children, I sometimes feel like an unconventional woman.

Freddie: You haven't conformed.

Celia: It is just a humanness. To care.

Freddie: My experience was really out of kilter with how other people felt about knitting and design. I think that's when I started to really think about all these associations and how I don't associate knitting with the domestic.

I never intended to subvert knitting. It was never, “I'm gonna go out there and really stir this up.” I'm just doing what feels right.

Celia: But I also think that's what's so great about your work. It does feel right. We talk about this with students, about integrity or authenticity.

I feel like we talk with students often about not only their methods of making, but also their ways of engaging with material ideas, colour, communication, that is correct for them. And that's the challenge.

Freddie: As opposed to trying to fulfil an expectation.

But then that's also true about your work when you are dealing with care, but not from a political viewpoint. It's the integrity of you and your practice, and it doesn't fulfil those other expectations that people are putting upon it, or they're trying to box you as this kind of person.

Celia: One of the big challenges I had when I was nursing was you had to care by the rules.

Celia’s needles. Photo: Sarah Bates

Paper piece detail. Photo: Sarah Bates

I was a nurse for 3 years, longer if you include the couple years when I worked as a care assistant. And I was very bad with being able to limit myself. I'm only allowed to…

Freddie: Care so much.

Celia: Yes. For practical reasons, because there was so much work and caring to do.

Freddie: I think that's why I couldn't teach in a school, because the needs and curriculum have boundaries. Whereas teaching at the RCA [Royal College of Art], we don't do it that way. What the students are doing sits so closely to what we do outside of the institution. I really like the melting between my practice and the students and the teaching. It's not possible to separate them.

Celia: Definitely. It's what I always liked about further study, like MA level study. As a student, but then also as a teacher, you are at a bridging moment where you’ve made a decision about somewhere you’re headed and there’s a lot of potential in study, but you’re not there yet.

Freddie: I think one of the things about going to study is being removed from the world.

Celia: Yes, ideally, students disappear into their studies.

Freddie: The making of textiles can go into any context, or the works can be used in any form. I get as much from meeting the students as I hope they get from me. It is a two-way relationship, which I find so stimulating. The longer I've been teaching, the more I've liked it, and the more I’ve come to enjoy that. And at all different ages, you bring different things to a teaching role.

When you first graduate, it's a very short bridge between you as a tutor and the student.

Celia: When I first started teaching, I was teaching 18-year-olds, so the age gap between us was small. Whereas now, with this project I just did with the five-year-olds, I'm the age of their parents.

Freddie: It’s not just about the students churning out good stuff. It's so much more than that. One of the things that I really realised the longer I teach is that each year I bring something different to it, because I'm a year older.

Each year, that little bridge I spoke about before, the one between you and the student, shortens. And by the time you're my age, with my life experience and education, you realise how different their experience is from yours, particularly now we have students from all around the world. It's a really dynamic job. You bring something else to it.

It’s fantastic, and it's a real privilege to work with other creative people.

They'll be carrying me out in a box.

Pieces from Celia’s Studio

Freddie’s Blanket

(Mended by Celia)

Freddie: It’s such a hard blanket, isn't it?

Celia: It's very old. But it's lasted like it works. It does the job.

Freddie: All the edges have come off. I really wouldn't be surprised if this hadn't been a wedding present for my parents.

Celia: You can feel how massive that hole is in there, but I didn't want it to show. For some reason with this blanket, it had such a nice square in a grid to it. I remember for ages worrying that I'd missed a hole, laying it out and worrying that I'd missed one.

It's such a tough blanket. The feel of it is not that of a friendly blanket, but it would be good for a picnic; yet, I would never dare sit on it.

Freddie: You spoke about that before, where the object that was a functional everyday object became art. Then you’ve made it special, and now I don't want to sit on it.

Celia: I get that feedback quite a lot these days. “You've transformed it from functional to functionless function.”

I find it really difficult when I go on panel discussions about the functionality of mending, because mine isn't functional. When the clothes transform, people don't want to wear them anymore.

Celia’s Paper Pieces

Celia: A friend came in yesterday and said, “Can I wear those paper jackets?” I was like, “What are you talking about?”

Freddie: How dare you! The arrogance of you.

Celia: I said, “Well, you can't wash them.”

It just always makes me laugh when people ask: “Can I wear it?” It doesn't even have any 3D quality.

I've been making this paper clothing, these paper silhouettes, probably for five or six years.

Freddie: Didn't you start with a swimming costume?

Celia: I made two. I made my mum one.

But the paper thing was really good. Then I made a couple more of them from other people's sweaters.

I was obsessed with Peter Pan, where he has the shadow that he tries to sew back onto his heels. It's the idea of making shadows of all these things I mend because they get returned to people, and I think about them, but I don't really have them around anymore.

Freddie: But you're not interested in the function?

Celia: Not remotely, no.

Freddie: You are interested in the repair of the whole and what that symbolises?

Celia: Yeah. And the opportunity to be close to someone through this thing.

Freddie: You're not trying to make it good again, in the functional way a garment can be good again.

We both see that as a really refute function. We both see that as a really overrated aspiration.

BECOME PART OF CELIA’S STORY

To support Celia and learn more about the incredible care she puts into every mend, consider purchasing her book, 'On Mending: Stories of Damage and Repair'.

It's available to buy online at Quickthorn Books or in-store at Loop, Ray Stitch and Trolley Books.

You can also follow Celia's mending journey on Instagram @celiapym to stay updated on her latest projects.